The most consequential decision Robert Kolker made in “Bad Art Friend” was telling it out of order.

Kolker’s version appears to be chronological, but he withholds crucial information until the third act. As a result, the internet has spent days debating who the titular B.A.F. of the story is.

Because I have a big project due this week, I spent those days in a procrastinatory frenzy, reading as many Dorland v. Larson legal documents as I could get my hands on. From my perspective, telling the story in linear time makes it far easier to take sides.

2005-2015: Kinda-Sorta Friends

Sonya and Dawn met in either 2005 or 2007, depending on which pdf you believe. They both lived in Boston at the time, ran in the same literary circles and were involved with a writing nonprofit called GrubStreet.

The nature of their friendship is one of the core elements of the ongoing legal case. Dorland claims they were close, sharing intimate conversations and spending significant time together. Larson claims that they were not. According to her lawyer, they have never been alone in a room together.

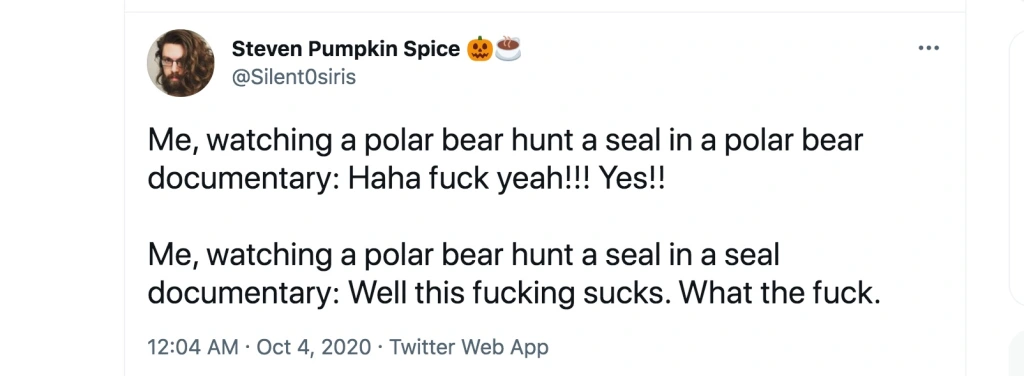

One of the most fascinating aspects of Bad Art Friend is the degree to which it acts as a Rorschach test. Chances are, you identify with one of the protagonists early in the story, then find yourself excusing their increasingly indefensible behavior. Cards on the table: At this point in the story, I’m with Dawn. I have always feared that my behavior is cringey in ways that I’m unaware of and that my friends discuss behind my back. This anxiety is particularly acute in professional settings, where I often don’t know the “rules” for social interaction and how to draw the line between my LinkedIn self and my actual personality.

My factual interpretation of these early years is that Dawn liked Sonya and thought they had a real connection. Sonya found Dawn obnoxious but didn’t want to make a Thing out of it because they inhabited the same small professional scene. My moral interpretation is that when someone you dislike considers you a close friend, that is a form of power. You don’t have to like them back, but you’re still obligated to treat them with a baseline of respect — even if they’ll let you get away with less.

Fast-forward to July 2015. Dawn has been away from Boston for four years. She keeps up with the old scene on social media but doesn’t have any direct contact with Sonya. She gives away her kidney to a stranger and sets up a Facebook group to update her close friends on the process. Dawn says this group contains 20-30 people, Sonya says it includes 250-300 and a screenshot in the legal filings (from years after it’s set up) shows it with 68 members.

This is where Dawn lost lot of readers in Kolker’s story. Setting up a Facebook group to (basically) brag about the good thing you did is bad enough. Dawn then wrote to Sonya to ask why she hadn’t engaged with any of the posts. According to Dawn, Facebook analytics showed that Sonya had seen them, but hadn’t liked or commented. Kolker also includes a brutal aside: During this time Dawn attended a writers’ conference where she bumped into numerous members of the Facebook group, few of whom brought up her charitable act.

“I left that conference with this question,” she tells Kolker, “Do writers not care about my kidney donation?”

I’m not going to defend Dawn exactly, but I’ll be honest about my emotional reaction to her. All of this is objectively cringe, but it’s also deeply human. Most people are smug and self-congratulatory after they volunteer at a soup kitchen or study abroad. It’s clear that Dawn gave away her kidney partly because she wanted other people to praise her. So what? She saved someone else’s life at moderate risk to her own health. Personally, I think that gives her a license to be obnoxious on social media for a few months afterwards.

Reaching out to Sonya to ask why she hadn’t liked any of her posts makes slightly more sense if you recall that Dawn considered her a close friend and saw the Facebook group as a small, private forum. This wasn’t a place where Dawn was posting public appeals for her friends to donate to charity or “Hey look I’m on the Jumbotron!” self-aggrandizement. She was doing that on her public Facebook page.

The private group was where she posted information about medical complications and more intimate dispatches — one of which was the text of the letter she sent to the end recipient of her “kidney chain.” To my knowledge, she never posted this letter anywhere publicly.

I honestly find all of this a bit baffling because it would never cross my mind to set up a private Facebook group, but I can easily imagine someone who, say, just had a baby wanting a forum to talk about their postpartum depression with a few close friends. Given the size of the group and Dawn’s expectations, it’s understandable that she would notice that one of the friends she invited into her confidence had viewed all of her posts but hadn’t responded or checked in on her.

I still think e-mailing Sonya to ask why she hadn’t engaged is fairly obnoxious, but in Dawn’s mind this was a close friend who was passively participating in a supportive forum yet wasn’t offering support. The pinned post on the Facebook group stated clearly that this was a place for Dawn’s close friends to track updates and read her private reflections. If that’s not your thing, the post said, feel free to leave at any time.

I couldn’t find her message to Sonya in the legal filings, but from later correspondence it seems she was doing a temperature-check. Is this something you’re interested in? Maybe you don’t have time right now or you think I made a rash decision. Rather than take the out, Sonya doubled down. She reiterated her friendship with Dawn, her support for the donation and her interest in staying in the group.

As for the writer’s conference, Dawn’s quote feels more sad than entitled to me. From her perspective, she had undergone a major surgery and was embarking on a new philanthropic project that was taking up a lot of her time. And yet her close friends, people she had entrusted with this information before she even got the surgery, didn’t seem like it was worth remarking on. Dawn even spotted Sonya at the writer’s conference but got the impression she was avoiding eye contact.

Again, imagine someone who just had a baby or got their master’s degree. It’s not unreasonable for them to expect their close friends to make some sort of comment about it.

I’m not going to defend Dawn’s general smugness nor condemn Sonya for disliking her. It really does seem like Dawn concocted a close friendship out of almost nothing, something she was probably doing with other members of their social circle too. That’s irritating behavior. But it’s nowhere near as immoral as what Sonya was about to do.

2015: Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V

So here’s where we stick with the timeline, in contrast to Kolker’s NYT story. According to later legal filings, Sonya began working on a short story based on Dawn’s kidney donation at almost exactly the time Dawn reached out to her: Summer of 2015.

“The Kindest,” she says in a filing, “is a fictional short story about an alcoholic, working class, Chinese-American woman who receives a kidney donated by a wealthy white woman.”

Around a third of a the way through the story, Sonya’s protagonist receives a letter from the “white savior” who donated her kidney. In the original version of the story, the one Sonya submitted to numerous publishers and recorded for Audible, this letter is almost identical to a letter Dawn posted on the private Facebook group.

Despite what Sonya will later tell her friends to make Dawn seem unreasonable, this wasn’t an honest mistake or written from memory or placeholder text that was left by accident. Sonya made only superficial tweaks to the text of Dawn’s letter. And she knew it: Months later she texted two friends, “I think I’m DONE with the kidney story but I feel nervous about sending it out b/c it literally has sentences that I verbatim grabbed from Dawn’s letter on FB. I’ve tried to change it but I can’t seem to — that letter was just too damn good.”

Now everything clicks into place. Sonya stayed in Dawn’s Facebook group, at least in part, to surveil and mock her. The legal filings include numerous exchanges where Sonya’s friends text her with some variation on “you’ll never guess what Dawn posted this time” and Sonya responds in turn.

Sonya’s short story was based on Dawn; an early draft even called the white-savior character “Dawn.” Everyone who knew them both and read the story knew exactly what was going on.

I don’t know whether this is illegal, but it is straightforwardly unethical behavior as a writer and immoral behavior as a human.

Sonya could have quietly unfollowed Dawn or refused to participate in the Burn Book group chats. She could have written a story where her contempt for Dawn was better-disguised, swapping out kidney donation for adopting kids from Ethiopia or running a marathon. She could have been honest with Dawn when she checked in: Look, I know you think we’re friends but we’ve grown apart since you left Boston and it’s probably best if we just move on.

Instead, she wrote the story, sent it off, went through the editing process and got it published — all while lying to Dawn’s face about the nature of their relationship. And, bafflingly, without bothering to change the text she lifted from Dawn’s letter.

2016-2018: Confrontation

Now we come back to Kolker’s timeline. A year later, in the summer of 2016, Dawn’s friend (in the snitch-tag of the decade) left a comment on her Facebook page saying that Sonya had just done a reading of a short story featuring a kidney donation.

Dawn was hurt. Her friend hadn’t seemed interested in her own story of donating a kidney. And now she wrote one without saying anything to her?

Dawn reached out to Sonya to say she had heard about the story and asked if she could read it. Sonya said it wasn’t finished and denied that it had anything to do with Dawn’s experience or the Facebook group. Dawn’s donation was a jumping off point, but it was only the seed of a story that had grown in a different direction.

Kolker saves this for his third-act twist, but Sonya was lying. Not only was the story finished, it had already been published. She was working with an actor to record an audio version. Behind the scenes, Sonya updated the text of the letter to make it look less identical to Dawn’s and e-mailed Audible to ask them to re-record that part of the story.

In their e-mail exchange — in which Dawn comes off as needy and Sonya comes off as icy — the two had come to a truce and ended by reiterating their commitment to remaining friends. Dawn had no reason to disbelieve Sonya about the “The Kindest” having nothing to do with her, so she seems to have let it drop. She didn’t even read it: The story came out in 2017 but Dawn ignored it, either because she expected it would stress her out or because she didn’t want to pay for a copy, depending on whether you believe her legal filings or her interview with Kolker.

Then, roughly a year after their e-mail exchange, “The Kindest” was published without a paywall on the website of American Short Fiction. A month or so after that, Dawn decided to finally read it.

She was shocked. While Sonya had updated the wording of the letter significantly since the original version, Dawn immediately recognized the structure and tone of her own.

There were also some lingering similarities. Dawn’s letter, for example, had said, “I focused the majority of my mental energy on imagining and celebrating you.” [she underlined this part on Facebook]. Sonya’s fictional letter said “I found a profound sense of purpose, knowing that your life depended on my gift.” [also underlined in the printed text]. Perhaps most damningly, Sonya’s fictional white savior ends her letter with “Kindly,” Dawn’s standard e-mail sign-off.

Dawn was livid. And here’s where my sympathies start to shift.

2018: Lawyers Get Involved

It was clear to Dawn that Sonya had written a story about an entitled, oblivious, self-aggrandizing kidney donor based on her own life and lifted from her Facebook posts. Over the following months, Dawn attempted to scorch the earth underneath Sonya’s writing career.

First she reached out to American Short Fiction to tell them that Sonya’s story included passages plagiarized from her own work. The tone of these letters is, frankly, obnoxious. Dawn threatens legal action and suggests that ASF give her space for an essay to accompany Sonya’s story.

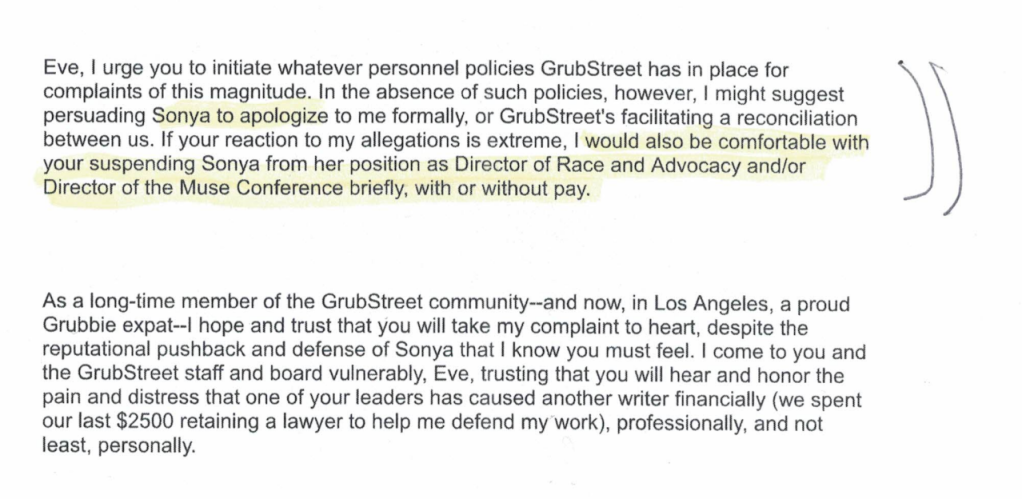

Dawn was marching into Stalingrad. She filed a copyright on her original letter, hired a lawyer and pitched the story to journalists. She reached out to more than a dozen mutual acquaintances and literary institutions. Dawn claims that some of these letters were just to inquire about their plagiarism policies, but the legal filings also include requests to remove Sonya from her position at literary organizations.

A month after ASF published the story online, Dawn learned that it was slated to be included in One City One Story, an anthology published by the Boston Book Festival. (In one of many darkly funny asides in the legal filings, Dawn only learns this in advance because Sonya puts it on her personal website before the festival announces it. Writers!).

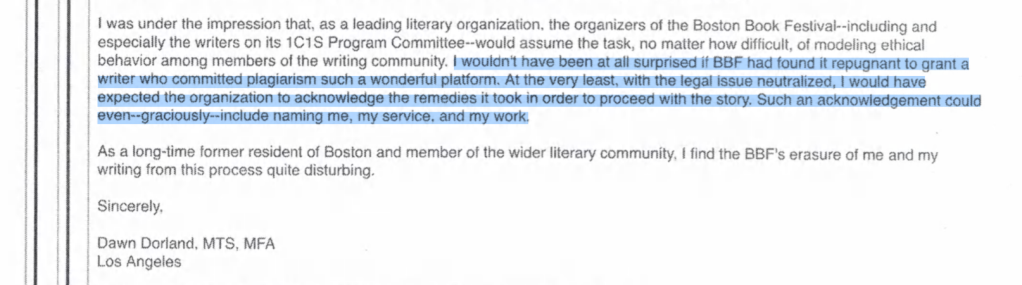

Again Dawn put on her viking helmet, tasking her lawyer to send a cease and desist notice and threatening the festival with $150,000 in damages. Her correspondence with the festival organizers is also dripping with condescension.

Here we are again at straightforwardly unethical and immoral behavior. Local book festivals do not have deep pockets. According to correspondence included in the legal filings, the festival organizers spent more than $10,000 defending themselves. Whenever they tried to meet Dawn’s demands, she ratcheted them up. In the end, they canceled the festival and destroyed every copy of the anthology.

I should note, however, that there’s some blame for Sonya here too. As the festival organizers point out (in some of the saltiest e-mails I’ve ever seen), she never should have submitted a story that was part of a copyright dispute with another author. She knew Dawn was going after the ASF and, let’s remember, that Dawn’s claim was correct. She had based her character on Dawn and her letter on Dawn’s letter.

Considering that they knew a lot of the same people and worked with the same literary organizations, did she really think Dawn was just never going to find out? I keep marveling at how little Sonya seemed to consider Dawn’s feelings or the possibility of a copyright claim during the two-plus years she spent writing and revising this story.

2018-Present: Let’s Go To Court

It’s not clear to me who formally hired a lawyer first, but Sonya sued first, filing a claim against Dawn for “tortious interference” — sabotaging her financial relationships with publishers, writers’ workshops and, it appears, the entire American literary establishment. Dawn had stumbled across the original version of the story, the one with the super copy-pasted version of her letter, online and countersued for copyright infringement and emotional distress.

I have no idea whether any of Dawn’s or Sonya’s actions constitute legally actionable behavior and I don’t care. Bad Art Friend is a morality play — that’s what makes it so interesting to talk about — and the legal system is only relevant as a weapon wielded by one protagonist against the other.

This is, as far as I can tell, how Dawn and Sonya have spent the last three years, suing and countersuing each other. Over 7,000 pages of discovery evidence have now been entered into the record. The original lawsuits have become numbingly boring meta-lawsuits about whose counsel said what and which plaintiff owes discovery evidence to the other. Even I, a procrastination Olympian, could not muster up the gumption to untangle or give a shit about these technicalities.

The only thing I’m sure of is that by now, both women have spent tens of thousands of dollars fighting in court about a short story that sold for $425. They have also, as of this weekend, achieved the worst kind of fame, the kind where people on the internet boil your entire life down to your most regrettable relationship and argue about whether you are a bad person or a terrible one.

So here I am, a person on the internet, delivering my verdict. From where I sit, identifying the Bad Art Friend is easy. In the early years, it is Sonya. She abused Dawn’s trust to mock and gaslight her, while lying to their mutual friends to make her look even worse.

In the later years, it is Dawn. Someone you considered a friend turned your intimate reflections into a derogatory short story and humiliated you in front of your social circle. That sucks, but turning your hurt feelings into a career vendetta and a years-long legal battle is sucky behavior too. Dawn’s letters to Sonya’s publishers acknowledge that this mattered to her primarily as an emotional betrayal by a friend, not a professional transgression by a fellow writer. She could have written a gossipy Medium post or a retaliatory short story or started a spicy group chat. But to me, cutting her losses and walking away was (and is) the most graceful option.

I have no idea how the rest of this story is going to play out. It is probably not worth a New York Times feature and absolutely not worth the weekend I have spent reading blurry screenshots in PACER pdfs. Whatever happens, I sincerely hope that they both keep it off of Facebook.